By Will Foiles

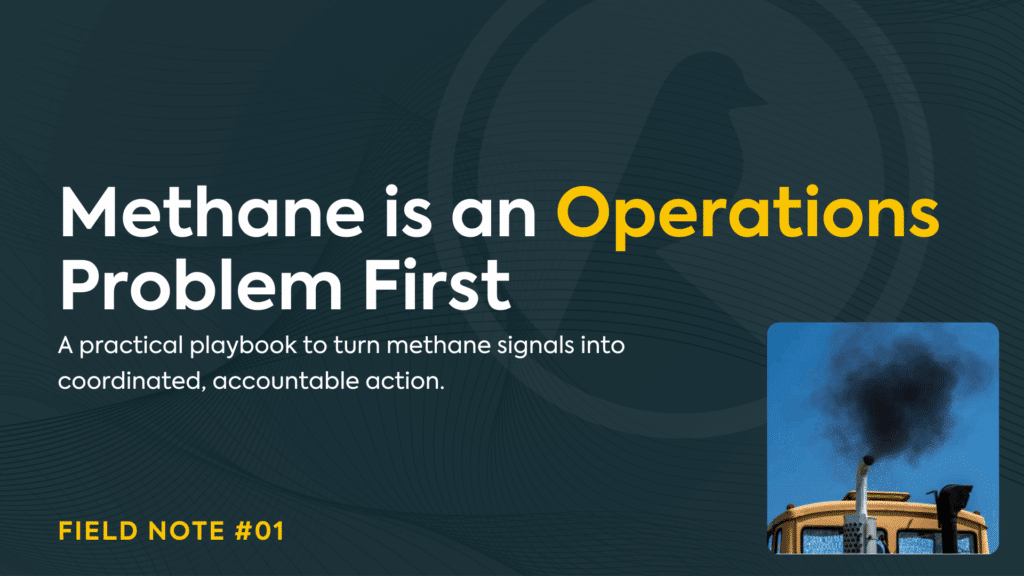

When most people hear “methane,” they only think of ESG reports, regulatory requirements, and climate commitments. I don’t. I see product loss, reliability risks, and safety hazards. A plume signals a new piece of potentially relevant information; an early warning that something is out of spec and could cost you money. Basically, it’s someone’s product escaping into the atmosphere. And methane is a valuable product and an explosive gas. Treat leaks like work orders, not headlines.

Follow a truck with smoke coming from its tailpipe, and you understand the story. Sure, one could make such smoke a story about local air quality or the environment, but there’s a far more pertinent reason that the truck owner should pay attention. The fact is that the engine isn’t functioning correctly. The driver can fix it on their schedule, or they may eventually be stranded on the side of the road, which will likely be at an inopportune time, incurring additional costs, both personal and financial. Methane emissions are similar. A plume may indicate mis-assembly, corrosion, worn seals, off-spec engines, or practices that lead to downtime, increased risk, and unnecessary costs.

Measurement is just the first step; true innovation is moving from measurement to operational intelligence—the “so what?” of what’s happening and what should happen next. The goal isn’t another dashboard; it’s a coordinated hand-off, enabling the right people to act and showing what has changed.

The truth is that there are numerous ways to uncover these operational issues, each with distinct advantages and trade-offs. Are you only looking to find larger, more costly operational problems, or are you also interested in properly accounting for all of your emissions? In clean air, methane levels are about 1.8 to 1.9 ppm. If your tools can’t detect small bumps above that, you will miss the “pennies” that add up over time, meaning you’re unable to account for all emissions. With sufficient sensitivity and enough measurements, you can state things like “this site emitted about 4,000 kg of methane in July” and rely on that for planning, budgeting, and voluntary reporting. But the next question can and should be, is such a capability worth the cost? And on which facilities is it advantageous to have such a capability, if any?

Arguably, more important is the operationalization of such information. After identifying an anomaly that requires attention, how do you coordinate with service personnel through a structured, automated workflow? You’ll likely want to maintain a clear chain of custody to track each person’s actions and timing. To recap, here’s the practical playbook we follow:

- Use the right combination. Periodic measurement (satellites, aerial flyovers, etc.) and ground-based approaches are different tools for different purposes. Satellites offer broad views and capture major events. Ground measurements provide continuous data at a specific site. Select the option that best suits your situation on any site after incorporating a range of objectives and constraints, ensuring an effective combination of the data.

- Make sense of it in context. Combine measurements with operational data already tracked, including flows, temperatures, pressures, workovers, tank pickups, equipment condition, and other activities, to understand the “so what?”

- Close the loop and show the result. Because the work often touches a wide range of functions spanning the office to the field, keep the chain of custody tight. Come back later to re-measure and show the change and use the same data flows to generate reports that people can trust.

This isn’t about waiting for the following rule. The best operators fix leaks now because it protects people and assets, stops product loss, and when regulations arrive, they are already in a good place. Think seatbelts and unleaded gasoline: what was once debated becomes standard practice.